#charmer edward is canon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

This is 90% of my basis for AHITN Seagull characterization btw

#charmer edward is canon#it's a bit buried but it's in there#anyway as you can probably guess the 'ask' is proceeding apace and is turning more into 'full blown literary analysis essay'#the railway series#ttte edward#shoutout to duck who's just blatantly rooting for injuries#2+8

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mist On The Water

Mist On The Water https://ift.tt/TK2l0Bo by hiraeth_ish The war is winding down but the attempts on Harry's life are not. Ridding himself of the horcrux has released a raw power in Harry that many admire, but some want to eliminate. Caught up in a mess of paranoia and exhausted from a year of constant battle, Harry needs an escape. Following the trail of an old letter from Ephraim Black, he takes refuge in Forks. Going by a new name, Harry settles in a town where no one knows who he is and, more importantly, no-one from his old life can hunt him down. It is typical Potter Luck that a coven of vampires have claimed the land and the ridiculously good looking blonde seems to be obsessed with Harry. As he navigates his new relationship with his distant cousin Jacob Black, tries to recover from the trauma of war and get a handle on his powerful new magic, Harry discovers that happiness might just be within his reach. But enemies are circling and Harry must fight for his life and those he loves once more. Words: 3569, Chapters: 1/1, Language: English Fandoms: Harry Potter - J. K. Rowling, Twilight Series - All Media Types Rating: Not Rated Warnings: Creator Chose Not To Use Archive Warnings Categories: F/F, F/M, M/M Characters: Harry Potter, Luna Lovegood, Kreacher (Harry Potter), Jacob Black, Jasper Hale, Alice Cullen, Charlie Swan, Bill Weasley, Ron Weasley, Hermione Granger, Draco Malfoy, Edward Cullen, Emmett Cullen, Carlisle Cullen, Esme Cullen, Billy Black, Teddy Lupin Relationships: Jasper Hale/Harry Potter, Carlisle Cullen/Esme Cullen, Hermione Granger/Draco Malfoy, Emmett Cullen/Rosalie Hale Additional Tags: Master of Death Harry Potter, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder - PTSD, Implied/Referenced Child Abuse, Vampires, Harry Potter Epilogue What Epilogue | EWE, Major Jasper Whitlock, Alternate Universe - Canon Divergence, War Veteran Harry Potter, Hurt/Comfort, Angst with a Happy Ending, True Mates, Soulmates, Magically Powerful Harry Potter, Anxiety, Nightmares, Parselmouth Harry Potter, Harry Potter is Bad at Feelings, Protective Jasper Hale, Boys In Love, Idiots in Love, Fluff and Smut, harry is a charmer despite his best efforts, Potter Luck, Harry Potter Has a Saving People Thing, Traumatized Harry Potter, Elemental Magic, Wandless Magic (Harry Potter), Blood and Injury, Jasper is Obsessed with Feeding Harry via AO3 works tagged 'Hermione Granger/Draco Malfoy' https://ift.tt/BdzjaFN December 30, 2023 at 10:16PM

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nemo's OCs - Part 1

Title: "Iron Wills" Pairing: David the Vampire & Robyn Irons &Tatiana Volkova Fandom: The Lost Boys/Fables Main Song: Karliene - We're The Devils Year of Creation: 2021

Title: "The Larks' Song- Book 1: Ghosts of Another Life" Pairing: Loki Laufeyson & Grace Caterina Caruso Fandom: MCU Song: "I will always find you" by Karliene Year of Creation: 2015

Title: "The Larks' Song - Book 2: Tinkering Hearts" Pairing: Anthony Edward Stark & Grace Caterina Caruso Fandom: MCU Song: "Bleeding Love" by Leona Lewis Year of Creation: 2015

Title: "The Larks' Song- Book 1: Boulevard of Broken Dreams" Pairing: James Buchanan Barnes & Veronica Ottavia Caruso Fandom: MCU Song: "Amaranthine" by Amaranthe Year of Creation: 2015

Title: The Larks' Song- Book 2 : The Nightingale and The Rose" Pairing: Kaecilius the Immortal & Veronica Ottavia Caruso Fandom: MCU/Original Song: "Let Us Burn" by Within Temptation Year of Creation: 2015

Title: "The Werewolf's Charmer " Pairing: Armand the Vampire & Artemis the Werewolf Fandom: "Interview with the Vampire (1994)/VTM" Song: "Ghost of a Rose" by Blackmore's Night Year of Creation: 2005

Title: "Are you afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?" Pairing: Chris Redfield & Thalia Thériaud Fandom: Resident Evil Song: "Love Story" by Indila Year of Creation: 2022

hi everyone.

I was just having a bit of fun, the other week, looking for some gifs for some of my Canon/OC pairings that I have developed throughout the years, and this is the result. I had the chance to look into my old files, and had some fun revising my old ocs, that I still hold so dear to my heart.

so here you have a small overview of some of my brainchildren and their beloveds. I chose the gifs with care, because I wanted to try to convey, at least partially, the nature of the relationship between the two (or three) characters and a little bit the personality of the OCs themselves.

--Nemo

#Nemo babbles#ocs#The Lost Boys#Interview with the Vampire#MCU#Resident Evil#if you have any question or any curiosity about them do not hesitate to send me an ask#I am always happy to babble#once I feel better about AC I might post even my AC brainchildren#if and when I feel better#Nemo's ocs#my ocs

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

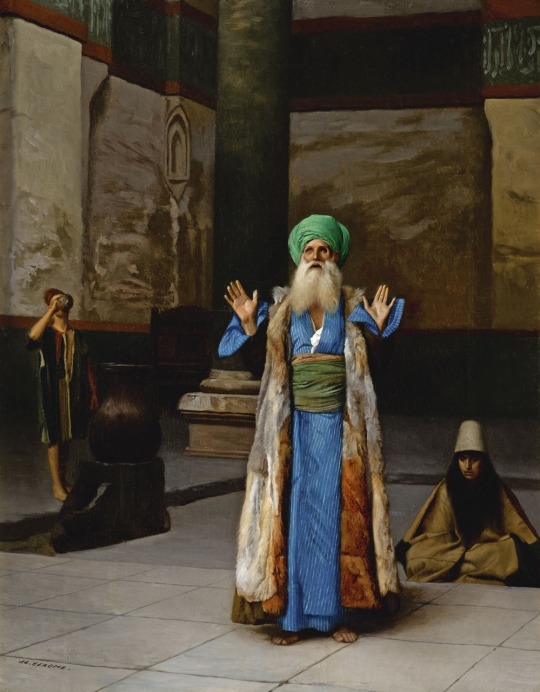

ORIENTALISM

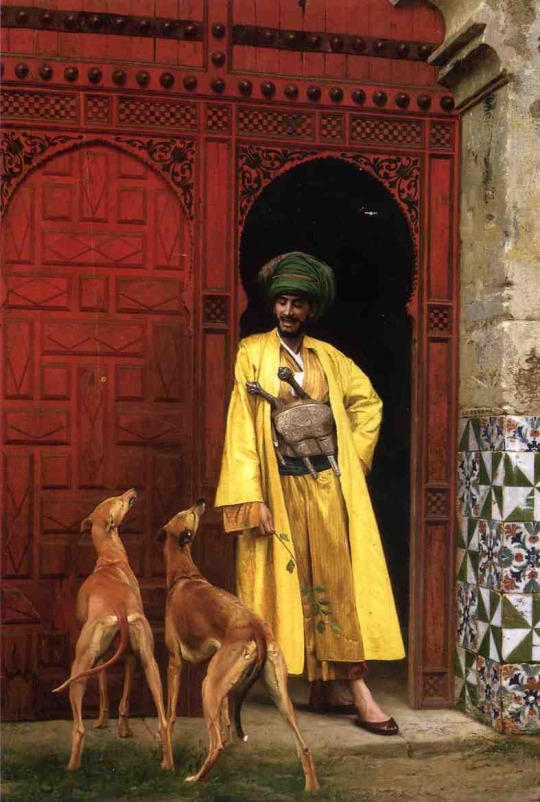

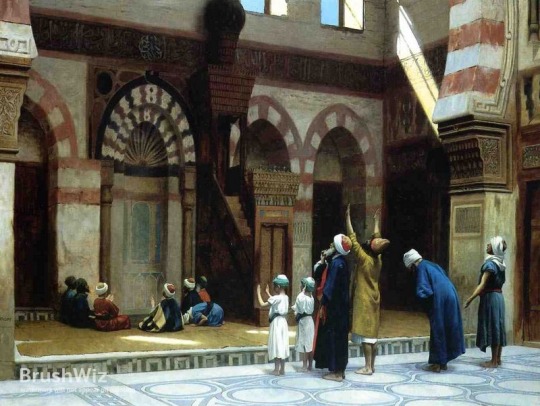

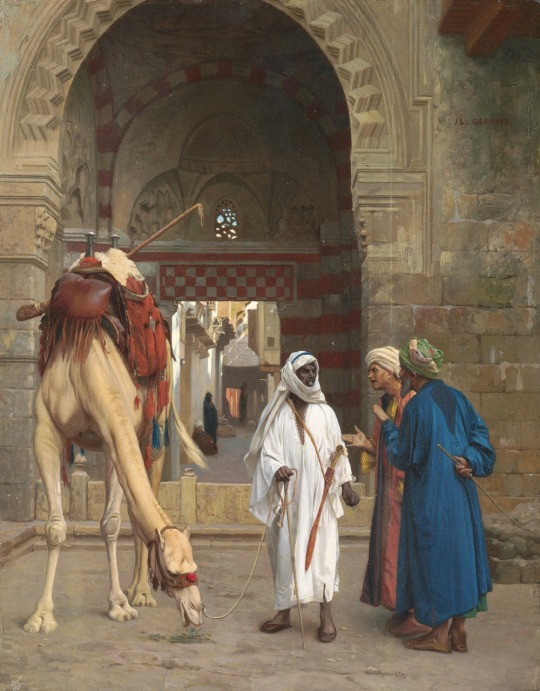

After decades of disinterest and contempt, Orientalist art, and the art of Jean-Léon Gérôme in particular, is once again in demand among collectors and fetching high prices at auction. Both Sotheby's and Christie's have Departments of Orientalist art, with Sotheby's proclaiming its "proud history of selling exceptional Orientalist paintings at auction" and Christie's "demonstrating the timeless appeal of this aesthetic." The April 2019 Sotheby's Orientalist auction totaled £5.4 million; Christie's sold Gérôme's portrait of Markos Botsaris (seen above) for $3.3 million in the same month.

Within the academy, however, Gérôme's standing in the western canon has yet to recover from the publication of Edward Said’s Orientalism in 1978. Although Said never discusses the visual arts, his influential critique of western colonialist and imperialist representations of the “oriental” other is easily and profitably applied to Gérôme’s pictures of life in the Arab and Muslim worlds (the book’s cover illustration is by Gérôme). Gérôme’s vast œuvre, in many ways, sustains such a critique. Considered an expert on Near Eastern culture by Napoléon III, a member of the Légion d’Honneur, an academician of the Institut de France, the President of the Société des Peintres Orientalistes Français, and as a popular and regular exhibitor of orientalist painting at the salons, Gérôme had a greater influence on French conceptions of Near Eastern culture and official policies on colonial affairs than most artists had on any area of society.

Neo-classical history painting employed monumental scale and meticulous facture to depict edifying episodes of ancient history with grandeur and clarity. Like most mid-century academic painters, Gérôme retains the large format and high-gloss finish, but takes a novelistic, rather than exemplary, approach to his subject matter.

His painstakingly detailed images of mosques, markets and hamams that serve as settings for his orientalist pictures were based on copious oil sketches made and feature artifacts acquired over numerous trips to the eastern Mediterranean. Taken together, the details gives the impression of obsessive, empirical observation—a realism intended to reassure the viewer of the authenticity of the picture‘s content.

What one sees, however, is, for the most part, anecdotal depictions of unheroic, daily life. The mundane ativities depicted—arguments, daily prayers, playing with pets, casual conversations—recall genre painting and do not provide models of virtuous behaviour. Instead, these accessible, familiar scenes of everyday life invite the viewer to identify, to a certain extent, with an alien culture. Like Alma-Tadema’s Victorianized Romans, Gérôme encourages us to see ourselves in the oriental other. The colony is a reflection of imperial overlord.

The implied transcultural humanity suggested by Gérôme’s choice of relatable subjects should not, however, be overstated. The depictions of the unheroic persons insufficiently engaged in unimportant activities is part of larger denunciation of “oriental” culture in general. Gérome paints scene after scene of idleness, lassitude, and inertia—men lean against buildings, sit stupified with a hookah, squabble in the streets, dogs sleep in the sun, and limp women loll around the baths while mosques crumble in the background.

The overwhelming sense of stagnation, of a falling off from past greatness and achievement, that pervades the Near East of Gérôme’s pictures is best expressed by a picture a group of travelling merchants and their camels resting in heaps at the feet of a colossal, still erect, statue of an Egyptian pharaoh. The backwards, indolent nature of the contemporary oriental other is, of course, a primary justification for western colonialism. “The white man’s burden,” as Rudyard Kipling memorably put it, involves the imposition of western improvements and notions of progress on the benighted subaltern.

Sexual malaise goes hand in glove with stagnation in the orientalist imaginary. Gérôme’s more lurid works (like The Snake Charmer) and the images of the harem and slave market rely on a queasy eroticism and to shock, disgust, but also titillate, their western audiences. While it is difficult to determine if Gérôme is aware of the degree to which these pictures reflect anxieties about 19th-century French sexual mores, it is very clear that they reflect popular and official views and opinions about the inhabitants of the colonies.

The technical virtuosity on display in Gérôme’s paintings is astonishing, but no amount of bravura can detoxify his orientalist ideology. The apparent lack of self-awareness concerning painting’s role in the construction of that ideology is one of the criteria that, in general, distinguished academic artists from the Impressionist avant garde, whom Gérôme detested. To be sure, he condemned Manet and Monet on formal, not ideological, grounds, but that actually gets to the heart of the matter. Manet attempted to depict the realities of the French colonial adventure in the Execution of Maximilien but found the subject too appalling to bring to compositional completion. Gérôme's art, by contrast, is characterized by its high degree of finish no matter how meretricious the subject.

#orientalism#imperialism#colonialism#jesn-léon gérôme#academic art#french painting - 19thc.#second empire

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was 85 years ago this week, in October 1934, that Mark Sandrich’s The Gay Divorcee was released in theaters across the country. That occasion would normally have been just another movie release except it marks a significant moment in movie history. The Gay Divorcee, you see, was the first starring picture for Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. While cinema has given us many memorable romantic movie couples, only one was so memorably romantic in dance.

The Gay Divorcee is my favorite of the Astaire Rogers pictures thanks in large part to its hilarious supporting cast including Alice Brady, Edward Everett Horton, Erik Rhodes, and Eric Blore who supply laughs galore in a story we’d see over and over again later in the 1930s as the Astaire and Rogers film canon picked up speed. Here we see Mimi Glossop (Rogers) trying to get a divorce from her estranged husband. Her Aunt Hortense (Brady) suggests she consult with attorney Egbert Fitzgerald (Horton) with whom Hortense has a romantic history. The fumbling lawyer suggests a great way for Mimi to get a quick divorce is for her to spend the night with a professional co-respondent and get caught being unfaithful by the private detectives hired for the task. Except, Egbert forgets to hire the detectives. As the co-respondent Egbert hires Rodolfo Tonetti (Rhodes) who is supposed to introduce himself to Mimi by saying “Chance is a fool’s name for fate,” but the Italian can’t keep the line straight, which never fails to make this fan roar with laughter.

“Fate is the foolish thing. Take a chance.”

In the meantime, staying in the same hotel is dancer Guy Holden (Astaire) who falls for Mimi the moment they had an uncomfortable meeting on the ship from England. Guy is determined to make Mimi his while she mistakes him for the co-respondent. It’s quite the confusing premise that serves the talent of the cast and Astaire-Rogers pairings on the dance floor, which made the trip to the movies the magical experience these movies surely were.

Fred Astaire reprised his role from the stage play The Gay Divorce for The Gay Divorcee. Censors insisted that The Gay Divorce be changed to The Gay Divorcee, because a gay divorce was no laughing matter. Erik Rhodes and Eric Blore, who played the waiter in typical snooty fashion, also reprised their roles from the stage version. Cole Porter wrote the music for the stage production, but only one of his songs, “Night and Day” was retained for the movie.

The Gay Divorcee won one Academy Award, the first ever Best Original Song for “The Continental” with music and lyrics by Con Conrad and Herb Magidson respectively. The film was also nominated for Best Picture, Best Art Direction, Best Sound, Recording, and Best Music Score for Max Steiner, then head of the sound department at RKO. While award recognition is great, the place The Gay Divorcee holds in history is much more important. As mentioned, this was the first movie where Fred Astaire’s and Ginger Rogers’ names appear above the title. This film also sets the stage quite nicely for subsequent Astaire-Rogers movies, which often followed the same formula. First, Fred’s character usually falls for Ginger’s at first sight and he is often annoying to her. In The Gay Divorcee, for example, she has her dress caught in a trunk while he attempts to flirt. In��Top Hat (1935) he wakes her up with his tap dancing in the room above hers. In Swing Time (1936) he asks her for change of a quarter only to ask for the quarter back a bit later.

Most Fred and Ginger movies also have mistaken identity central to the plot and some are set in lavish surroundings, extravagant art deco sets, “Big White Sets” as they are called, and include travel to exotic places. The world in these pictures is rich and cultured and never fail to offer an escape from reality.

More importantly, most of the Astaire-Rogers movies feature dances that further the characters’ story together, all are supremely executed, beautifully orchestrated, and emoted to a tee. Through dance Fred and Ginger express love, love lost, anger, giddiness, joy, despair, tragedy. The movies usually feature at least two main routines for the couple, one a fun, lighthearted affair and the other a serious, dramatic turn, depending on where in the story the dance takes place. These dance routines take precedence in the films above all other elements and are, ultimately, what create the Astaire-Rogers legend, each its own priceless gem. For this dance through history the focus is on the dance routines, which were born out of the RKO story.

RKO was born RKO Radio Pictures in October 1928 as the first motion picture studio created solely for the production of talking pictures by David Sarnoff and Joseph Kennedy as they met in a Manhattan oyster bar. Radio-Keith-Orpheum (RKO) resulted from the merger of the Radio Corporation of America, the Film Booking Offices of America, and the Keith-Albee-Orpheum circuit of vaudeville houses.

In its first year, RKO did well by producing about a dozen pictures, mostly film versions of stage plays. The studio doubled that number the following year and was established as a major studio with the Academy Award-winning Cimarron (1931) directed by Wesley Ruggles. Unfortunately, that film’s success did not result in money for the studio. That year RKO lost more than $5 million, which resulted in the hiring of David O. Selznick to head production. Selznick immediately looked to stars to bring audiences into theaters. The first place he looked was the New York stage where he found and contracted Katharine Hepburn whom he placed in the hands of George Cukor for Bill of Divorcement (1932) opposite John Barrymore. Hepburn became a star and the movie was a hit, but RKO’s fortunes did not improve making 1932 another difficult year. Enter Merian C. Cooper and a giant ape. David O. Selznick had made Cooper his assistant at RKO.

The idea of King Kong had lived in Cooper’s imagination since he was a child, but he never thought it could come to fruition until his time at RKO. It was there that Cooper met Willis O’Brien, a special effects wizard who was experimenting with stop motion animation.

King Kong premiered in March 1933 to enthusiastic audiences and reviews. RKO’s financial troubles were such, however, that even the eighth wonder of the world could not save it. David O. Selznick left RKO for MGM and Merian Cooper took over as head of production tasked with saving the studio. Cooper tried releasing a picture a week and employing directors like Mark Sandrich and George Stevens. Of the two Sandrich made an important splash early with So This Is Harris! (1933), a musical comedy short that won the Academy Award for Best Short Subject. This short paved the way for RKO’s memorable musicals of the decade, the first of which introduced future megastars Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers as a dancing duo.

“I’d like to try this thing just once” he says as he pulls her to the dance floor.

“We’ll show them a thing or three,” she responds.

And they did. For the movie studio permanently on the verge of bankruptcy Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers proved saving graces. Pandro S. Berman, who produced several of the Astaire-Rogers movies, said “we were very fortunate we came up with the Astaire-Rogers series when we did.”

Fred Astaire was born Frederick Austerlitz II on May 10, 1899 in Omaha, Nebraska. Fred began performing at about the age of four with his older sister Adele. Their mother took them to New York in 1903 where they began performing in vaudeville as a specialty act. Of the two it was Adele, by all accounts a charmer on stage and off, who got the better reviews and was seen as the natural talent.

By the time Fred was ten years old, he and his sister were making about $50 a week on the famed Orpheum Circuit. As they traveled the country, their reputation grew and by 14 Fred had taken over the responsibility of creating steps and routines for their act. He also hunted for new songs as he was able, which led to a chance meeting in 1916 with then song plugger George Gershwin. Although the two did not work together then, they’d have profound effects on each other’s careers in the future, including the Astaires headlining George and Ira Gershwin’s first full-length New York musical, Lady, Be Good! in 1924.

Unlike her driven brother, Adele did not even like to rehearse. For Fred’s constant badgering to rehearse she ascribed him the nickname “Moaning Minnie.” Fred later admitted the nickname fit because he worried about everything. Between Fred’s attention to detail and Adele’s charm for an audience, the Astaire’s reviews usually read like this, “Nothing like them since the flood!”

Fred and Adele made it to Broadway in 1917 with Over the Top, a musical revue in two acts, and never looked back. Their other hits in New York and London included the Gershwin smash, Funny Face (1927), where Adele got to introduce “‘S Wonderful” and the Schwartz-Dietz production of The Band Wagon (1931), Adele’s final show before retiring to marry Lord Charles Cavendish in 1932. At the time she and her brother Fred were the toast of Broadway.

The Astaires, Adele and Fred

After his sister retired, Fred starred in Cole Porter’s A Gay Divorce, his last Broadway show before heading west to Hollywood where he was signed by David O. Selznick at RKO. Legend goes that of Fred Astaire someone in Hollywood said after watching his screen tests, “Can’t act; slightly bald; can dance a little.” If true, those are words by someone who had a terrible eye for talent, but I doubt they are true because at the time Fred Astaire was a huge international star. The likelihood that someone in Hollywood didn’t know that is slim. David O. Selznick had seen Fred Astaire on Broadway and described him as “next to Leslie Howard, the most charming man on the American stage.” What was true is that Fred Astaire did not look like the typical movie star. He was 34 years old at the time, an age considered old for movie stardom. In fact, Astaire’s mother insisted he should just retire since he’d been in the business from such a young age. We can only be thankful he ignored her request.

Not sure what to do with him, or perhaps to see what he could do, Selznick lent Astaire to MGM where he made his first picture dancing with Joan Crawford in Robert Z. Leonard’s Dancing Lady (1933). Flying Down to Rio experienced some delays, but it was ready to go after Dancing Lady so Fred returned to RKO to do “The Carioca” with a contract player named Ginger Rogers.

By the time Fred Astaire made his first picture, Ginger Rogers had made about 20. She was under contract with RKO and excelled at sassy, down-to-Earth types. In 1933 Ginger had gotten lots of attention singing “We’re in the money” in Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933) and in 42nd Street. She did not have top billing in either of those, but the public noticed her.

Ginger Rogers was born Virginia Katherine McMath in Independence, Missouri on July 16, 1911. Her first few years of life were confusing ones. Her parents were divorced and Ginger was kidnapped by her father until her mother, Lelee (or Lela), took him to court. In need of a job, Ginger’s mother left her with her grandparents while looking for a job as a scriptwriter.

Lelee met and married John Rogers in 1920 and, for all intents and purposes, he became Ginger’s father. The family moved to Dallas where, at the age of 14, Ginger won a Charleston contest, going on to become Charleston champion dancer of Texas. The prize was a 4-week contract on the Vaudeville Interstate circuit. Lela took management of her daughter and put together an act called “Ginger and Her Redheads.” Ginger continued to perform on her own after the Redheads were disbanded eventually going to New York where she was seen by the owner of the Mocambo night club who recommended her to friends for the Broadway show Top Speed.

Ginger was making two-reelers in New York when she was offered a Paramount contract making her feature appearance in Monta Bell’s Young Man of Manhattan (1930) starring Claudette Colbert. At about that time, she was cast as the lead in the Gershwin musical Girl Crazy, which – by happenstance one afternoon – offered her the opportunity to dance with Fred Astaire for the first time ever. Astaire had been brought in to the Girl Crazy production to see if he could offer suggestions for the routines. Ginger was asked to show him one of the main numbers to which he said, “Here Ginger, try it with me.”

After that Ginger and Lela headed to Hollywood and the picture business in earnest. Ginger made a few forgettable pictures for Pathé before being cast as Anytime Annie in 42nd Street and singing that number about money in Golddiggers of 1933. Both of those gave Ginger Rogers ample opportunity to show off her comedic skills. These types of parts, funny flappers, were definitely in the cards for Ginger Rogers until fate intervened when Dorothy Jordan, who was scheduled to dance “The Carioca” with Fred Astaire in Flying Down to Rio, married Merian C. Cooper instead. Ginger was by now under contract with RKO and was rushed onto the set of Flying Down to Rio three days after shooting had started.

“They get up and dance” in 1933

The stage direction in the original screenplay for Flying Down to Rio simply read, “they get up and dance.” Ginger Rogers was billed fourth and Fred Astaire fifth showing she was the bigger star at the time. In looking at Astaire and Rogers doing “The Carioca” in Flying Down to Rio one doesn’t get the impression that these are legends in the making. Ginger agreed as she wrote in her memoir that she never would have imagined what was to come from that dance. “The Carioca” is exuberant, youthful, and fun, but certainly lesser than most of the routines the couple would perform in subsequent films. I say that because we can now make a comparison. At the time audiences went crazy for “The Carioca” and the dancers who performed it, their only number together in the Flying Down to Rio and only role aside from the comic relief they provide. The picture was, after all, a Dolores Del Rio and Gene Raymond vehicle.

Doing the Carioca in Flying Down to Rio

Hermes Pan’s first assignment at RKO was to find Fred Astaire on stage 8 to see if he could offer assistance. Fred showed him a routine and explained he was stuck in a part for the tap solo in Flying Down to Rio. Hermes offered a suggestion and another legendary movie pairing was made. Pan worked on 17 Astaire musicals thus playing a key role is making Fred Astaire the most famous dancer in the world.

Pan explained that he went to early previews of Flying Down to Rio and was surprised to see the audience cheer and applaud after “The Carioca” number. The studio knew they had something big here and decided to capitalize on the Astaire-Rogers pairing.

When RKO approached Fred Astaire about making another picture paired with Ginger Rogers, Astaire refused. After years being part of a duo with Adele, the last thing he wanted was to be paired permanently with another dancer. If he was to do another picture he wanted an English dancer as his partner, they were more refined. Pandro Berman told him, “the audience likes Ginger” and that was that. Astaire was at some point given a percentage of the profits from these pictures and the worries about working with Ginger subsided. Ginger’s contribution to the pairing was not considered important enough to merit a percentage of the profits.

The Gay Divorcee (1934)

The Gay Divorcee offers ample opportunity to fall in love with the Astaire-Rogers mystique. The first is a beautiful number shot against a green screen backdrop, Cole Porter’s “Night and Day.” Fred as Guy professes his love for Mimi (Ginger), mesmerizing her with dance until she is completely taken by the end. He, so satisfied, offers her a cigarette.

Later in the film the two, now reconciled after a huge mix-up, dance “The Continental.” The song is introduced by Ginger who is swept off her feet to join the crowd in the elaborate production number. Needless to say Fred and Ginger clear the floor with outstanding choreography. “The Continental” sequence lasts over 17 minutes, the longest ever in a musical holding that record until Gene Kelly’s 18-minute ballet in An American in Paris in 1951. “The Continental” was clearly intended to capture the excitement of “The Carioca” and exceeds that by eons with enthusiasm and gorgeous execution by these two people whose chemistry is palpable. No one could have known if either Fred or Ginger could carry a movie, but The Gay Divorcee proved they were stars of unique magnitude. For 85 years dance on film has never been bettered and that’s why I celebrate this anniversary with all the enthusiasm I could muster as my contribution to The Anniversary Blogathon sponsored by the Classic Movie Blog Association (CMBA), which is celebrating its tenth year of classic love.

Doing The Continental in The Gay Divorcee

Fred always gets a solo number in these pictures, by the way and, as you’d expect, they’re wonderful. Many times these take place in hotel rooms all of which – luckily – have fantastic floors for tap dancing. In addition, The Gay Divorcee has the added attraction of a routine with Edward Everett Horton and Betty Grable, who has a small part in the picture.

Fred Astaire and Hermes Pan would begin work on the routines up to six weeks before the principal photography was scheduled to start on the pictures. Pan played Ginger’s part and would teach her the routines once she arrived to start rehearsals. Her part was long and arduous and Fred Astaire always said he admired her work ethic as she gave everything she had to make those routines memorable and match him move for move. Fred was also impressed by Ginger being the only one of his female partners who never cried. As they say, she did everything he did “backwards and in heels,” which by the way, is a phrase born in the following Frank and Ernest cartoon.

The unfailing result of their work together is absolute beauty in human form. Ginger Rogers completely gave herself to Fred Astaire, was entirely pliable to his every whim in dance. This is why they became legend. Fred may have partnered with better dancers and I certainly cannot say whether that’s true or not, but what he had with Ginger Rogers was special. The Gay Divorcee was only the beginning.

As for working with Fred again, Ginger had no worries. She enjoyed the partnership and the dancing and was fulfilled by doing various other parts at the same time. While Fred and Hermes worked on the routines she was able to make small pictures for different studios appearing in seven in 1934 alone.

Roberta (1935)

Fred and Ginger’s next movie together is William Seiter’s Roberta where they share billing with one of RKO’s biggest stars and greatest talents, Irene Dunne. Here, Fred and Ginger have the secondary love affair as old friends who fall in love in the end. As they do in most of their movies, Fred and Ginger also provide much of the laughs. The primary romantic pairing in Roberta is between Dunne and Randolph Scott.

The film’s title, Roberta is the name of a fashionable Paris dress shop owned by John Kent’s (Scott) aunt and where Stephanie (Dunne) works as the owner’s secretary, assistant, and head designer. The two instantly fall for each other.

Huck Haines (Astaire) is a musician and John’s friend who runs into the hateful Countess Scharwenka at the dress shop. Except Scharwenka is really Huck’s childhood friend and old love, Lizzie Gatz (Rogers). Fred and Ginger are wonderful in this movie, which strays from the formula of most of their other movies except for the plot between Irene Dunne and Randolph Scott, which is actually similar to that of other Astaire-Rogers movies. Again, aside from the dancing Fred and Ginger offer the movie’s comic relief and do so in memorable style with Ginger the standout in that regard.

There are quite a few enjoyable musical numbers in Roberta. Huck’s band performs a couple and Irene Dunne sings several songs including the gorgeous “When Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” and a beautiful sequence on stairs during a fashion show to “Lovely to Look At,” which received the film’s only Academy Award nomination for Best Music, Original Song. That number transitions into a Fred and Ginger duet and dance to “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” followed closely by an exuberant finale number.

Fred and Ginger in Roberta

Early in Roberta, at the Cafe Russe, Ginger is delightful singing “I’ll be Hard to Handle” with the band. She and Fred follow with a supremely enjoyable duet with their feet, a routine where each answers the other with taps. I believe there were requests for them to re-record the taps after the live taping as you can hear Ginger laughing during the routine, but Fred insisted to leave it as is. The result is a relaxed, wonderfully entertaining sequence I hadn’t seen in years. The pantsuit Ginger wears during this number is fabulous.

I’ll Be Hard to Handle routine in Roberta

Later, Ginger and Fred sing a duet to “I Won’t Dance” with Fred following with an extraordinary solo routine. This may be my favorite of his solo sequences, which includes an unbelievably fast ending.

Astaire in Roberta

Fred Astaire was perfection on the dance floor and, as many have said, seemed to dance on air. None of it came without excruciating hard work, however. Astaire was known for rehearsing and losing sleep until he felt every movement in every sequence was perfect. He stated he would lose up to 15 pounds during the rehearsals for these films. Clearly, nothing had changed since his days preparing for the stage with his sister.

Fred Astaire fretted over routines constantly. He could not even stand looking at the rushes himself so he would send Hermes Pan to look and report back. Astaire admitted that even looking at these routines decades later caused him angst. Of course, his absolute dedication to perfection, pre-planning even the smallest detail of every dance number, resulted in much of the legend of Fred and Ginger. Fred’s demands on set also made the pictures epic among musicals. Astaire insisted, for instance, to shoot every single sequence in one shot, with no edits. He also insisted that their entire bodies be filmed for every dance number and that taps be recorded live. He was known to say that either the camera moved or he moved. One of the cameramen at RKO who worked on the Astaire-Rogers pictures said that keeping Fred and Ginger’s feet in the frame was the biggest challenge. All of these Fred Astaire stipulations ensured that the performances are still moving many decades after they were filmed and all of them are as much a statement in endurance as they are in artistry.

Top Hat

Directed by Mark Sandrich, Top Hat is the first film written expressly for Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers by Deight Taylor and Alan Scott and feels bigger from its catchy opening sequence on forward than the other movies in the series to this point. This is perhaps the most well regarded of the Astaire-Rogers movie pairings and it’s no wonder because it’s delightful even though it shares several similarities with The Gay Divorcee. Joining Fred and Ginger once again are Edward Everett Horton in the second of three Fred and Ginger pictures he made, Eric Blore in the third of five, and Erik Rhodes in his second. To my delight Rhodes dons that wonderful, hilarious Italian accent, which by the way, got him barred by Mussolini. Joining the group in this picture is Helen Broderick as Madge Hardwick, Horton’s wife.

The story in Top Hat begins when Fred as Jerry Travers meets Ginger as Dale Tremont when he wakes her up by tap dancing in the hotel room above hers. She is naturally annoyed, but warms up to him fairly quickly the next day as he seeks her favor with Irving Berlin’s “Isn’t This a Lovely Day?” when the two are in a gazebo during a rainstorm. The song ends in a wonderful dance sequence that starts off as a challenge, but warms to affection. I should add we see here what we see in many Astaire-Rogers routines that is so darn exciting – when they don’t touch. The gazebo number is not as emotionally charged as others the couple executes because it is the lighthearted one in the picture, the one during which he woos her with dance. By the end of this number she is sold on him and what prospects may lay ahead.

It’s a lovely day to be caught in the rain from Top Hat

Unfortunately, after the gazebo number some confusion ensues as Dale believes Jerry is married to one of her friends. This is the requisite mistaken identity. It is Horace Hardwick (Horton) who’s married, not Jerry. Some innocent games and trickery take place before Dale is hurt and Jerry has to win her over once again. Then heaven appears.

“Heaven, I’m in heaven And the cares that hung around me through the week Seem to vanish like a gambler’s lucky streak When we’re out together dancing cheek to cheek”

These songs are standards for a reason. It just does not get better than that.

To continue the story – at the insistence of Madge Hardwick, Dale and Jerry dance as he sings those lyrics to her. She is mesmerized, wanting to believe him wearing that famous feather dress. They move onto a terrace in each other’s arms as the music swells.

A gorgeous, sexy backbend during Cheek to Cheek in Top Hat

Once again, the song is over and her heart is stolen. She’s seduced. And so are we.

One of the few times Ginger seriously disagreed with Fred concerning a routine was her stance on the feather dress for the “Cheek to Cheek” sequence. Fred hated it. During the number feathers went everywhere, including in his face and on his tuxedo. Ginger designed the dress and insisted she wear it, despite the cost of $1,500 worth of ostrich feathers. She was right. While you can see feathers coming off the dress during the number, none are seen on Fred’s tuxedo, but it doesn’t matter because it moves beautifully and adds immeasurably to the routine.

The feather dress didn’t stay there. In fact, it stayed with Ginger for some time as thereafter, Astaire nicknamed her “Feathers.” After what Ginger described as a difficult few days following the feather dress uproar, she was in her dressing room when a plain white box was delivered. Inside was a note that read, “Dear Feathers. I love ya! Fred”

Fred Astaire has two solo routines in Top Hat, “No Strings” at the beginning of the movie, the tap dance that wakes Dale, and “Top Hat, White Tie and Tails,” a signature production number considered one of his best.

Following in the tradition of “The Carioca” and “The Continental,” Top Hat features “The Piccolino,” an extravagant production number with song introduced by Ginger who said that Fred was supposed to sing the tune and hated it so he told Sandrich to give it to Ginger. In any case, she and Fred join the festivities with only their feet visible heading toward the dance floor, reminiscent of the movie’s opening sequence. It’s quite the rush as you see their feet advancing toward the dance floor, I must say.

“The Piccolino” is lively and fun, a terrific routine with a fun ending as the two end the number by sitting back at their table with Ginger having to fix her dress, a beautiful dress that made it to the Smithsonian.

Fred and Ginger doing The Piccolino

Top Hat premiered at New York’s Radio City Music Hall to record crowds. Added security had to be sent to the venue to ensure order. The movie went on to gross $3 million on its initial release, and became RKO’s most profitable film of the 1930s.

Follow the Fleet (1936)

Mark Sandrich was back to direct Follow the Fleet, which I have a huge affection for. The Irving Berlin score in this film is superb with songs that take me back to my childhood and the memory of watching them on Saturday nights on our local PBS station. Fred, Ginger, Sandrich and the crew of Follow the Fleet heard about the record numbers of moviegoers attending Top Hat as they gathered to begin shooting this movie. The excitement certainly inspired them to make Follow the Fleet the cheerful, energetic movie it is. Although, Ginger hoped that by this, their third movie together, Mark Sandrich would recognize her worth it was not to be. She discusses his dislike of her a lot in her book.

Like in Roberta, Fred and Ginger’s relationship in Follow the Fleet is that of the secondary romantic couple supplying the laughs in the film despite the fact that they get top billing. The primary romance here is the one between Harriet Hilliard (in her first feature film) and Randolph Scott. The story is simple, Bake Baker (Astaire) and Bilge (Scott) visit the Paradise Ballroom in San Francisco while on Navy leave. At the ballroom are Connie Martin (Hilliard), who is immediately taken with Bilge, and her sister Sherry (Rogers), the dance hostess at the ballroom who also happens to be the ex-girlfriend of Bake’s. Sherry and Bake reunite by joining a dance contest and winning (of course), but it costs Sherry her job.

In the meantime, Connie starts talking about marriage to Bilge who is instantly spooked sending him into the arms of a party girl. Bake tries to get Sherry a job in a show, which entails a mistaken identity amid more confusion until things clear up and the two are successful, heading toward the Broadway stage. The confusion here comes by way of some bicarbonate of soda, in case you’re wondering.

Follow the Fleet is a hoot with several aspects straying from the usual Fred-Ginger formula. To begin, Fred Astaire puts aside his debonair self and replaces him with a much more informal, smoking, gum-chewing average guy. It’s enjoyable seeing him try to be common. Fred opens the movie with Berlin’s wonderful “We Saw the Sea,” the words to which I remembered during the last viewing, quite the surprise since I had not seen Follow the Fleet in decades. Later in the movie he gets another solo tap routine on deck of his ship with fellow seamen as accompaniment. Both instances are supremely enjoyable as one would expect.

Fred during one of his solo routines in Follow the Fleet

Ginger does a great rendition of “Let Yourself Go” with Betty Grable as a back-up singer. A bit later there’s a reprise of the fabulous song during the contest, the dance reunion of Bake and Sherry. According to Ginger, a search through all of Hollywood took place in hopes of finding other couples who could compete with Fred and her. This may already be getting old, but here you have another energetic, enjoyable routine by these two masters. The whistles from the crowd at the Paradise Ballroom show the audience enjoy it as well.

The Let Yourself Go routine during the dance contest in Follow the Fleet

As part of an audition, Ginger gets to do a solo tap routine, a rarity in these movies and it’s particularly enjoyable to watch. Unfortunately, Sherry doesn’t get the job as a result of the audition even though she’s the best the producer has seen. Thinking that he’s getting rid of her competition (mistaken identity), Bake prepares a bicarbonate of soda drink, which renders the singer incapable of singing. Sherry drinks it and burps her way through the audition.

Sherry during the rehearsal, a solo tap for Ginger in Follow the Fleet

Now rehearsing for a show, Bake and Sherry sing “I’m Putting All My Eggs in One Basket” followed by a wonderfully amusing routine where Ginger gets caught up in steps leaving Fred to constantly try to get her to move along. During the number the music also changes constantly and they have fun trying to stay in step be in a waltz or jazz or any number of music moods. This routine is a rare one for Fred and Ginger whose dance sequences are usually step perfect. It looks like they have a blast with this including a few falls and a fight instigated by Ginger.

“Eggs in One Basket” routine from Follow the Fleet

Fred and Ginger follow the comical exchange in “I’m Putting All My Eggs in One Basket,” with one of their greatest sequences, another rarity in that this one happens out of character for both in the movie. The wonderful “Let’s Face the Music and Dance” and the routine to it make as iconic an Astaire-Rogers sequence as has ever put on film. The song and the performance tell a mini story outside of the confines of the plot. This is a grim tale executed with extraordinary beauty as we see two suicidal people happen upon each other and are saved from despair through dance. Again, kudos to Berlin’s genius because the lyrics of this song are sublime.

“There may be trouble ahead But while there’s moonlight and music And love and romance Let’s face the music and dance”

Ginger is a vision as Fred guides her across the dance floor. The dance starts off with a sway, they are not touching, he’s leading her, but she’s despondent at first, unable to react to his urging that there is something to live for. As that beautiful music advances she responds and in the process conquers demons. The routine ends as the music dictates in dramatic fashion with a lunge, they are both now victorious and strong. Magnificent. The movie concludes minutes later because…what more is there to say?

“Let’s Face the Music and Dance” Fred and Ginger

Ginger in beaded dress for “Let’s Face the Music and Dance”

Ginger is wearing another legendary dress in the “Let’s Face the Music and Dance” routine. Created by one of her favorite designers, Bernard Newman, the dress weighed somewhere between 25 and 35 pounds. The entire thing was beaded and moved beautifully along with Ginger. Fred Astaire told the story of how one of the heavy sleeves hit him in the face hard during the first spin in the dance. They did the routine about 12 times and Sandrich decided on the first. If you look closely you can see Fred flinch a bit as Ginger twirls with heavy sleeves near his face at the beginning of the dance, which is affecting, beautifully acted by both, but particularly Ginger in the arms of Fred Astaire.

Lucille Ball plays a small role in Follow the Fleet and can be seen throughout the film and a couple of times during the “Let’s Face the Music and Dance” sequence. Also, Betty Grable makes an appearance in a supporting role. Harriet Hilliard sings two songs in Follow the Fleet as well, but to little fanfare.

By Follow the Fleet Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers were top box office draws as a team. America was in love with Fred and Ginger. And they still hadn’t reached the apex of dance.

Swing Time (1936)

Swing Time was directed by George Stevens, his first musical, made when he was the top director at RKO Pictures. As I watched these films in succession I noticed something I never had before, Fred and Ginger’s dancing in Swing Time is more mature than in previous films. The emotionally-charged “Never Gonna Dance” sequence has always been my favorite, but I had never considered that it is because Astaire and Rogers are at their peak. This, they’re fifth starring outing as a pair, is their best.

The plot of Swing Time is similar to that of Top Hat to include the ever-present mistaken identity theme, but this movie is wittier and more inventive and clever surrounding memorable songs by Dorothy Fields and Jerome Kern. The story here begins as dancer and gambler, Lucky Garnett (Astaire) arrives late for his own wedding to Margaret Watson (Betty Furness). Angry at the young man’s audacity, the father of the bride tells Lucky that the only way he can marry his daughter is to go to New York and become a success. Lucky heads East with his lucky quarter and constant companion Pop Cardetti (Victor Moore).

Once in New York the stage is set for a chance meeting between Lucky and Penny Carroll (Rogers). The encounter leads to the first routine in the movie to the glorious “Pick Yourself Up” at the dance academy where Penny works as an instructor. The exchange leading up to the dance sequence is quite enjoyable as Lucky makes believe he can’t dance as Penny tries in vain to teach him. His fumbling on his feet causes her to be fired by the furious head of the dance studio, Mr. Gordon (Eric Blore). To make it up to Penny, Lucky pulls her to the dance floor to show Gordon how much she has taught him and she delights in seeing his amazing dancing ability. The routine that ensues is energetic, fun, and the movie’s acquaintance dance after which Penny is completely taken with Lucky.

During the “Pick Yourself Up” routine in Swing Time

Watching Ginger transition from angry to incredulous to gloriously surprised to such confidence that the dance floor can’t even contain them is simply wonderful. As the dance progresses her joy grows naturally illustrated by such details as throwing her head back or giggling as Fred, who’s the wiser, wows her. And she, in turn, gives Gordon a few hard looks as he sits there making memorable Eric Blore faces. At the end of the dance their relationship is different and Gordon is so impressed he gets them an audition at the Silver Sandal Nightclub where they enchant the patrons and are hired. Incidentally, since Fred’s mood, shall we say, is what initiates and dictates these routines he has little emotional change through these mini stories. The journey is mostly all hers.

Before they do the nightclub act, Lucky sings “The Way You Look Tonight” to Penny while her hair is full of shampoo. The song won the Academy Award for Best Music, Original Song. Penny and Lucky are now in love. That night at the nightclub, Penny tells Lucky that bandleader Ricardo Romero (Georges Metaxa) has asked her to marry him many times so it’s no surprise when Romero squashes their chance to perform. That is until Lucky wins Romero’s contract gambling and sets the stage for the “Waltz in Swing Time”

“The Waltz in Swing Time” seems to me to be one of the most complex of the Astaire-Rogers dance sequences. Performed at the gorgeous art deco club, this routine is as airy as it is masterful. Fred and Ginger lovingly looking at each other throughout as twists and turns and light taps happen around them. Gosh, they are awe-inspiring.

The Waltz in Swing Time

The next day Lucky does all he can to avoid a love-making scene with Penny. He’s in love with her, but remembers he’s engaged to another woman and hasn’t told her. Meanwhile Pop spills the beans to Mabel (Helen Broderick, the fourth wheel in this ensemble.) A kissless Penny and a frustrated Lucky sing “A Fine Romance” out in the country and Ginger once again gives a lesson in acting. I’ve noted in other posts about how acting in song is never taken too seriously by people and this is another example. Ginger Roger’s reviews in these films were often mediocre with the praise usually going entirely Astaire’s way. Admittedly, Astaire-Rogers films are not dramatic landscapes that allow for much range, but the fact that Ginger manages believable turns in the routines and in all of the sung performances should be noted. She had an air of not taking the films and roles too seriously, but still managed a wide range of emotion, particularly when the time came to emote in dance. That only made her all the better and often the best thing in the movies aside from the dancing.

Fred Astaire has a wonderful production number, “The Bojangles of Harlem,” in Swing Time even though he performs in blackface. The number is intended to honor dancers like Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson who were influential to Fred Astaire. Aside from Fred’s indelible dancing in the sequence, the number is memorable for introducing special effects into Fred Astaire dance routines as he dances with huge shadows of himself. The effect was achieved by shooting the routine twice under different lighting. “Bojangles of Harlem” earned Hermes Pan an Academy Award nomination for Best Dance Direction.

As our story continues – Penny and Lucky are definitely into each other and Ricardo is still wooing Penny when Margaret shows up to spoil the festivities. Actually, she comes to tell Lucky she’s in love with someone else, but doesn’t have a chance to say it before Penny is heartbroken.

And so here we are…we see Penny and Ricardo talking. Given the situation with Lucky – his impending marriage and his losing their contract while gambling – she feels she has no choice but to marry Ricardo. Lucky walks in. Two heartbroken people stand at the foot of majestic stairs as he begins to tell her he’ll never dance again. Imagine that tragedy. The music shifts to “The Way You Look Tonight” and “The Waltz in Swing Time” throughout. Ginger, who had gone up the stairs, descends and the two walk dejectedly across the floor holding hands. The walks gathers a quiet rhythm until they are in each other’s arms dancing. Still, she resists, attempts to walk away, but he refuses to let her go until she succumbs, joining him in energetic rhythm, two people in perfect sync as the music shifts to past moments in their lives together – shifts between loud and quiet, fast and slow, together and apart – mimicking the turmoil of the characters in that time and place.

Ginger’s dress here is elegantly simple as if not to detract from the emotion of the piece, which is intense. Everything about this routine is absolutely gorgeous.

Fred and Ginger split toward the end of the number, each going up an opposite staircase on the elaborate set. They reach the top where the music reaches its crescendo. The two dance, a flurry of turbulent spins. Until she runs off leaving him shattered. And me.

To my knowledge, the “Never Gonna Dance” sequence in the only one where a cut had to happen during the dance in order to get the cameras to the top of the stairs. This is the famous routine that made Ginger’s feet bleed. One of the crew noticed her shoes were pink and it turned out to be that they were blood-soaked. Also notable is that the number was shot over 60 times according to Ginger and several other people there. At one point George Stevens told them all to go home for the night, but Fred and Ginger insisted on giving it one more try. That was the take that’s in the movie. Once done the crew responded enthusiastically.

In the end of Swing Time, as is supposed to happen, Lucky manages to interrupt Penny’s marriage to Ricardo and makes her all his own.

Ginger looks stunning in Swing Time. For details on her Bernard Newman designs in the film I suggest you visit the Glam Amor’s Style Essentials entry on this film.

Despite the many wonderful things about Swing Time, the movie marked the beginning of audience response to Fred and Ginger movies declining. The movie was still a hit, but receipts came in slower than expected. The Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers partnership never quite gained the same momentum as it did up to this point in their careers together. Although the pair was still an asset for RKO and they had many more memorable on-screen moments to share.

Shall We Dance (1937)

In 1937 Astaire and Rogers made Shall We Dance with Mark Sandrich at the helm once again. Edward Everett Horton and Eric Blore are also on hand for the film that featured the first Hollywood film score by George and Ira Gershwin.

The plot of Shall We Dance is a bit convoluted, but still enjoyable. Fred plays Peter P. Peters a famous ballet dancer billed as “Petrov” who yearns to do modern dance. One day he sees a picture of famous tap dancer Linda Keene (Ginger) and sees a great opportunity to blend their styles. Similar to their other movies, Fred falls in love with Ginger at first sight. It takes her longer to recognize his graces, but eventually falls hard for him too. That is, after many shenanigans and much confusion when she gets angry and hurt and then he has to win her over again.

Fred has a terrific solo routine here with “Slap That Base,” which takes place in an engine room using the varied engine and steam sounds to tap to. Ginger later does an enjoyable rendition of the Gershwin classic, “They All Laughed (at Christopher Columbus),” which leads to a fun tap routine for the duo. For this Ginger is wearing that memorable flowered dress by Irene who dressed her for this movie. This “They All Laughed” sequence is where he woos her and where she cannot help falling for him.

Soon after “They All Laughed” Fred and Ginger call the whole thing off in the classic sequence that takes place in New York’s Central Park on roller skates. At this point in the story the tabloids have reported the two are married and, having fallen for each other, they don’t know what to do. “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off” was written by the Gershwins in New York prior to the making of Swing Time. The brothers brought the song with them to Hollywood and it works perfectly in the comedic scene with both Astaire and Rogers taking turns with verses of the catchy tune before starting the roller skating tap routine.

Unable to stop the rumors that they are married, Pete and Linda decide to actually marry in order to later divorce. The problem is that they’re both crazy about each other, which he demonstrates with one of the most romantic songs ever written, “They Can’t Take that Away From Me.” This song was a personal favorite of both Fred and Ginger. So much so, in fact, that the song was used again in their final film together, their 1949 reunion movie, The Barkleys of Broadway. “They Can’t Take That Away From Me” remains the only occasion on film when Fred Astaire permitted the repeat of a song previously performed in another movie.

George Gershwin died two months after Shall We Dance was released in May 1937. He was posthumously nominated for an Academy Award, along with his brother Ira, for Best Original Song for “They Can’t Take That Away From Me.”

The finale of Shall We Dance is an odd production number. Fred dances in front of dozens of women donning Ginger Rogers masks. Pete Peters decided if he can’t dance with Linda Keene then he’ll dance with many of the next best thing. The real Linda joins him for the final act, touched by his attempt to clone her. The end.

Carefree (1938)

Carefree is probably the Astaire-Rogers movie I’ve seen least and it was refreshing to take a new and improved look at it for this tribute. Mark Sandrich directs Fred and Ginger for the last time in this romantic comedy, the shortest of their films, which attempts a new story flavor for our stars with Irving Berlin tunes.

Stephen Arden (Ralph Bellamy) asks his Psychiatrist friend Dr. Tony Flagg (Astaire) to meet with his fiancée Amanda Cooper (Rogers). Immediately we know Arden’s in trouble because Ralph Bellamy never gets the girl, but anyway… Amanda is having trouble committing to marrying Stephen and agrees to see Tony who immediately decides she needs to dream in order for him to decipher her unconscious. After having all sorts of odd foods for dinner Amanda dreams, but of Dr. Tony Flagg, not Stephen. Embarrassed by her dream, Amanda makes up a weird tale, which leads Tony to think she has serious psychological issues that only hypnosis can fix. In slapstick style, Stephen comes by Tony’s office to pick up Amanda and without realizing she’s hypnotized lets her run free on the streets causing all sorts of havoc.

Fed Astaire does a terrific routine early in Carefree where he hits golf balls to music. I know nothing about golf, but recognize this is quite astounding. In a 1970s interview, Fred commented on the scene with some affection saying it was not easy and couldn’t believe he was asked to do another take when the balls were ending off camera.

Amanda’s dream allows for a beautiful, fantasy-like routine to Irving Berlin’s “I Used to Be Color Blind” made famous because Fred and Ginger share the longest kiss here than in any other one of their movies. It happens at the end of the sequence done in slow motion, which definitely causes swooning. About the kiss Fred Astaire said, “Yes, they kept complaining about me not kissing her. So we kissed to make up for all the kisses I had not given Ginger for all those years.” Fred was not a fan of mushy love scenes and preferred to let his kissing with Ginger in movies be alluded to or simple pecks, but he gave in partly to quell the rumors that circulated about he and Ginger not getting along. As Ginger told the story, Fred squirmed and hid as the two reviewed the dance and she delighted in his torture. She explained that neither of them expected the long kiss as it was actually a peck elongated by the slow motion. That day she stopped being the “kissless leading lady.”

The longest kiss Fred and Ginger ever shared on-screen from Carefree

By the way, Ginger is wonderful in the sequence when she’s hypnotized. She gets an opportunity to showcase her comedic skills in similar fashion than she does in Howard Hawks’ Monkey Business (1952) opposite Cary Grant.

At the club one evening Ginger kicks off “The Yam” festivities. According to Ginger this is another instance where Fred didn’t like the song so he pawned it off on her. Who could blame him? Silly at best, “The Yam” is a dance craze that never actually catches fire as it doesn’t have the panache of “The Continental.” These people give it all they have, however, and the evening looks like an enjoyable one. Or, at least I would have loved to be there. Of course Tony joins Amanda in doing “The Yam” before the crowd joins in. As an aside, Life Magazine thought Fred and Ginger doing “The Yam” was worthy of a cover on August 22, 1938.

After yamming it up, Amanda is determined to tell Stephen she’s in love with Tony, but he misunderstands and thinks she professes her love for him. Suddenly Stephen announces their engagement. It’s a total mess that Tony tries to fix through hypnosis, which backfires supremely. Thank goodness everything straightens itself out in the end.

Before getting to the final, exceptional routine in Carefree the supporting cast deserves a mention. Louella Gear joins the fun in Carefree as Aunt Cora, in the same vein as Alice Brady and Helen Broderick in Fred and Ginger movies before her. Hattie McDaniel makes a brief appearance albeit as a maid, but it’s better to see her than not and Jack Carson has a few enjoyable scenes as a brute who works at the psychiatrist’s office.

After Amanda tells Tony she’s in love with him, he hypnotizes her to hate him because he doesn’t want to betray Stephen. When Tony realizes he loves Amanda it’s too late, she’s left his office to be happy with Stephen, avoiding Tony at all costs. But at the club one evening, Tony manages to find a few moments alone with her outside and what results is a sexy number during which she’s completely under his spell. In fact, this may be Fred and Ginger’s sexiest routine. “Change Partners and Dance With Me,” which begins inside as she dances with Stephen, is another beautiful song from Irving Berlin, which received one of the three Academy Award nominations for Carefree for Best Music, Original Song. The other two Oscar nods were for Best Art Direction and Best Music, Scoring.

Howard Greer designed Ginger’s gowns for Carefree and the one she wears in the impassioned “Change Partners and Dance With Me” dance is absolutely stunning.

Ginger is under Fred’s Spell in Carefree

The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle (1939)

The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle directed by H. C. Potter is the ninth of ten dancing partnership films of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, the last of their musicals in the 1930s and for RKO, and the only one of their films based on a true story and real people.

Vernon and Irene Castle were a husband-and-wife team of ballroom dancers and dance teachers who appeared on Broadway and in silent films in the early 20th century. Hugely popular, the Castles were credited with popularizing ballroom dance with a special brand of elegance and style. Their most popular dance was the Castle Walk, which Fred and Ginger do in the movie. In fact, they replicate most of the Castle’s dances as closely to the original as possible. As you’d expect from Fred Astaire.

Irene Castle served as a Technical Advisor on The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle and the story goes that she eventually disowned the film because of the film’s lack of authenticity. In defense of some of the changes though, 1934 censorship restrictions were quite different than those in the 1910s. The differences affected costuming and casting at every level of the film. That said, Variety gave The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle a glowing review and the public received it warmly.

Ginger and Fred as Irene and Vernon Castle

It must be mentioned that The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle features two of the greatest character actors who ever lived. Edna May Oliver plays the Castle’s manager Maggie Sutton and Walter Brennan plays Walter, Irene’s majordomo, for lack of a better word, since she was a child. Both of these characters were changed dramatically for the film due to production code restrictions. The real Maggie Sutton (real name Elizabeth Marbury) was openly a lesbian and the real-life Walter was a black man. Neither of those suited the production code mind for broad appeal across the country.

Fred and Ginger do a fine job in this movie. The dances are pretty if not as elaborate as those Astaire and Rogers performed in their other movies. It is exciting to see them do a Tango, a dance I am particularly fond of. However, there is one other dance sequence in particular that moves me immensely, “The Missouri Waltz” at the Paris Cafe when Vernon returns from the war. The acting in the sequence is superb as you can feel the emotion jumping off of her as he picks her up in a gorgeous move during which she wraps herself around him. It’s stunning.

Ginger wrote in her book about the day they shot “The Missouri Waltz,” the last filmed in the movie and, to everyone’s mind, likely the last number she and Fred would ever do together. RKO was abuzz with rumors and people came from far and wide to watch them shoot it. They came from all around RKO, from Paramount and from Columbia to see this last dance. “This was a very dignified way to end our musical marriage at RKO.”

In 1939, after completing The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle, Astaire and Rogers split as you know. Astaire’s salary demands proved too much for RKO pictures. Fred Astaire went on to make movie musical magic in all manner of ways, both alone and with other outstanding talents, leaving a rich legacy of treasures. Ginger Rogers went on to prove herself a true quadruple threat. We knew by 1939 that she could sing, dance and be funny but now, determined to go into straight drama she reaches the pinnacle with an Academy Award-winning performance in Sam Wood’s, Kitty Foyle in 1940. I recognize Ginger’s dramatic talent in the time I spent watching the many dance routines she did with Fred Astaire, but in a time when movies were seen just once it’s difficult to think of other actors who make the transition from film genre to film genre so seamlessly as she did. Hers was a rare talent.

Since I already dedicated an entire entry to Fred and Ginger as The Barkleys of Broadway, Josh and Dinah Barkley, I will forego a full summary here. For now let’s relive the reunion.

Ten years after she made her last appearance on-screen with Astaire, Ginger Rogers walked onto the set of The Barkleys of Broadway. The cast and crew had tears in their eyes. This was special. She said her “hellos”, kissed Fred Astaire and they got to work. At first Ginger explained that Fred seemed disappointed. Judy Garland was scheduled to make the picture with him, but was replaced by Ginger. All of that doesn’t matter though because as a fan, I cannot fathom what it must have been like for audiences in 1949. If people are out of their minds excited about the release of a superhero film today, if audiences drool over a new and rehashed installment of Spiderman, imagine seeing legends together again after a ten-year sabbatical. I would have had to take a Valium. I get chills just thinking about it, and admit a bit of that happens when I watch The Barkleys of Broadway in my own living room. From the moment I see the opening credits, which are shown while the couple is dancing, quite happily – she in a gold gown and he in a tux, I mean, seriously, I’m verklempt right now. We are all happy to be together again.

Despite their great individual careers the magic of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers together cannot be replicated. And it wasn’t necessarily the dancing, or not the dancing alone, that made them a perfect pair. It was the glances, the touch, and the feel that made them magic. The spell of romance, real for the length of a composition, entranced. We all know Katharine Hepburn’s famous quote, “she gave him sex and he gave her class.” Well, Kate was not wrong. Fred Astaire was never as romantic as when he danced with Ginger. And Ginger, a down-to-Earth beauty, was never as sophisticated as when she danced with Fred.

Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers brought prestige to RKO when it was in desperate need of it and joy to a nation hungry for respite from tough times. In a six-year span they established themselves as the best known, best loved dancing partners in the history of movies and have remained there for 85 years. I’ll end with these words by Roger Ebert, “of all of the places the movies have created, one of the most magical and enduring is the universe of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.”

Sources:

The RKO Story

Ginger: My Story by Ginger Rogers

The Astaires: Fred & Adele by Kathleen Riley

As many Fred Astaire interviews as I could find.

Be sure to visit the Classic Movie Blog Association (CMBA) and The Anniversary Blogathon. There are many fantastic film anniversaries honored for this prestigious event.

85 Years of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers It was 85 years ago this week, in October 1934, that Mark Sandrich’s The Gay Divorcee…

#Astaire and Rogers Movies#Carefree#Flying Down to Rio#Follow the Fleet#Fred and Ginger#Fred and Ginger Movies#Fred Astaire#George Stevens#Ginger Rogers#Hermes Pan#Mark Sandrich#Pandro Berman#RKO Pictures#Roberta#Shall We Dance#Swing Time#The Barkleys of Broadway#The Gay Divorcee#The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle#Top Hat

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

We’ll make beautiful children together

Send ‘We’ll make beautiful children together’ and I’ll show you what our muses’ children would be like.

@sage-mcbaine

Name: Aiden Edwards McBaine

Gender: Male

General Appearance: Dark brown eyes and black hair.

Personality: Aiden is a goof ball and a cuddle bug. He loves being held and cuddled. He is a real charmer too, always has on a big smile and has the most infectious giggle. He can be a bit spoiled at times, he mostly throws a fit when he isn’t being held. His playful as well, he doesn’t mind sharing his toys as long as you play with him.

Special Talents: He is a very good climber.

Who they like better: BOTH!

Who they take after more: Kit

Personal Head canon: Aiden is a climber. Sometimes to the point where it can be dangerous and frankly a bit scary. Once he wanted some cookies before dinner and when his parents said no and placed the cookies on the counter top. They left the room for a mere moment and when the came back he had managed somehow to climb up onto the counter top and had already eaten three cookies. His face a crumbly mess but no look of shame. Just pure and utter pride!

Face Claim/Picture:

0 notes

Text

“What is more European, after all, than to be corrupted by the Orient?” - Richard Howard

What is the rationale behind the recent spate of revisionist or expansionist exhibitions of nineteenth-century art – The Age of Revolution, The Second Empire, The Realist Tradition, Northern Light, Women Artists, various shows of academic art, etc.? Is it simply to rediscover overlooked or forgotten works of art? Is it to reevaluate the material, to create a new and less value-laden canon? These are the kinds of questions that were raised – more or less unintentionally, one suspects – by the 1982 exhibition and catalogue Orientalism: The Near East in French Painting, 18oo-188o.’[1]

Above all, the Orientalist exhibition makes us wonder whether there are other questions besides the “normal” art-historical ones that ought to be asked of this material. The organizer of the show, Donald Rosenthal, suggests that there are indeed important issues at stake here, but he deliberately stops short of confronting them. “The unifying characteristic of nineteenth-century Orientalism was its attempt at documentary realism,” he declares in the introduction to the catalogue, and then goes on to maintain, quite correctly, that “the flowering of Orientalist painting… was closely associated with the apogee of European colonialist expansion in the nineteenth century.” Yet, having referred to Edward Said’s critical definition of Orientalism in Western literature “as a mode for defining the presumed cultural inferiority of the Islamic Orient … part of the vast control mechanism of colonialism, designed to justify and perpetuate European dominance,” Rosenthal immediately rejects this analysis in his own study. “French Orientalist painting will be discussed in terms of its aesthetic quality and historical interest, and no attempt will be made at a re-evaluation of its political uses.“[2]

In other words, art-historical business as usual. Having raised the two crucial issues of political domination and ideology, Rosenthal drops them like hot potatoes. Yet surely most of the pictures in the exhibition – indeed the key notion of Orientalism itself – cannot be confronted without a critical analysis of the particular power structure in which these works came into being. For instance, the degree of realism (or lack of it) in individual Orientalist images can hardly be discussed without some attempt to clarify whose reality we are talking about.

What are we to make, for example, of Jean-Leon Gerôme’s Snake Charmer, painted in the late 1860’s (now in the Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Mass.)? Surely it may most profitably be considered as a visual document of nineteenth-century colonialist ideology, an iconic distillation of the Westerner’s notion of the Oriental couched in the language of a would-be transparent naturalism. (No wonder Said used it as the dust jacket for his critical study of the phenomenon of Orientalism!)[3]. The title, however, doesn’t really tell the complete story; the painting should really be called The Snake Charmer and His Audience, for we are clearly meant to look at both performer and audience as parts of the same spectacle. We are not, as we so often are in Impressionist works of this period – works like Manet’s or Degas’s Café Concerts, for example, which are set in Paris – invited to identify with the audience. The watchers huddled against the ferociously detailed tiled wall in the background of Gérôme’s painting are as resolutely alienated from us as is the act they watch with such childish, trancelike concentration. Our gaze is meant to include both the spectacle and its spectators as objects of picturesque delectation.

Clearly, these black and brown folk are mystified – but then again, so are we. Indeed, the defining mood of the painting is mystery, and it is created by a specific pictorial device. We are permitted only a beguiling rear view of the boy holding the snake. A full frontal view, which would reveal unambiguously both his sex and the fullness of his dangerous performance, is denied us. And the insistent, sexually charged mystery at the center of this painting signifies a more general one: the mystery of the East itself, a standard topos of Orientalist ideology.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the insistent richness of the visual diet Gérôme offers – the manifest attractions of the young protagonist’s rosy buttocks and muscular thighs; the wrinkles of the venerable snake charmer to his right; the varied delights offered by the picturesque crowd and the alluringly elaborate surfaces of the authentic Turkish tiles, carpet, and basket which serve as décor – we are haunted by certain absences in the painting. These absences are so conspicuous that, once we become aware of them, they begin to function as presences, in fact, as signs of a certain kind of conceptual deprivation.

—

One absence is the absence of history. Time stands still in Gérôme’s painting, as it does in all imagery qualified as “picturesque,” including nineteenth-century representations of peasants in France itself. Gérôme suggests that this Oriental world is a world without change, a world of timeless, atemporal customs and rituals, untouched by the historical processes that were “afflicting” or “improving” but, at any rate, drastically altering Western societies at the time. Yet these were in fact years of violent and conspicuous change in the Near East as well, changes affected primarily by Western power – technological, military, economic, cultural – and specifically by the very French presence Gérôme so scrupulously avoids.

In the very time when and place where Gérôme’s picture was painted, the late 186os in Constantinople, the government of Napoleon III was taking an active interest (as were the governments of Russia, Austria, and Great Britain) in the efforts of the Ottoman government to reform and modernize itself. “It was necessary to change Muslim habits, to destroy the age-old fanaticism which was an obstacle to the fusion of races and to create a modern secular state,” declared French historian Edouard Driault in La Question d’Orient (1898). “It was necessary to transform (…) the education of both conquerors and subjects, and inculcate in both the unknown spirit of tolerance – a noble task, worthy of the great renown of France,” he continued.

In 1863 the Ottoman Bank was founded, with the controlling interest in French hands. In 1867 the French government invited the sultan to visit Paris and recommended to him a system of secular public education and the undertaking of great public works and communication systems. In 1868 under the joint direction of the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the French Ambassador, the Lycée of Galata-Serai was opened, a great secondary school open to Ottoman subjects of every race and creed, where Europeans taught more than six hundred boys the French language – “a symbol,” Driault maintained, “of the action of France, exerting herself to instruct the peoples of the Orient in her own language the elements of Western civilization.” In the same year, a company consisting mainly of French capitalists received a concession for railways to connect present-day Istanbul and Salonica with the existing railways on the Middle Danube.[4]

The absence of a sense of history, of temporal change, in Gérôme’s painting is intimately related to another striking absence in the work: that of the telltale presence of Westerners. There are never any Europeans in “picturesque” views of the Orient like these. Indeed, it might be said that one of the defining features of Orientalist painting is its dependence for its very existence on a presence that is always an absence: the Western colonial or touristic presence.

The white man, the Westerner, is of course always implicitly present in Orientalist paintings like Snake Charmer; his is necessarily the controlling gaze, the gaze which brings the Oriental world into being, the gaze for which it is ultimately intended. And this leads us to still another absence. Part of the strategy of an Orientalist painter like Gérôme is to make his viewers forget that there was any “bringing into being” at all, to convince them that works like these were simply “reflections,” scientific in their exactitude, of a preexisting Oriental reality.

In his own time Gérôme was held to be dauntingly objective and scientific and was compared in this respect with Realist novelists. As an American critic declared in 1873: